When I was a child, one of the books that captured my imagination most was Thor Heyerdahl’s “Kon-Tiki.” I remember curling up with its pages, wide-eyed at the thought of a handful of men crossing the Pacific Ocean on nothing but a raft made of balsa logs. The story felt larger than life—equal parts adventure novel and scientific experiment—but what struck me most was the idea that a bold idea, no matter how improbable, could actually be tested against the vastness of the sea.

Those pages filled my young mind with images of rolling waves, flying fish, and endless horizons. I used to imagine myself standing on that raft, watching the stars guide us through the night. The name “Kon-Tiki” stayed with me long after I closed the book, etched into memory as a symbol of courage and curiosity.

So when I finally found myself in Oslo, decades later, there was no question where I had to go.

Who Was Thor Heyerdahl?

Thor Heyerdahl (1914–2002) grew up fascinated by nature and human culture. Unlike many explorers of the 20th century who sought fame or conquest, Heyerdahl was searching for answers. His great question was: Were ancient civilizations capable of crossing oceans long before modern ships?

At a time when most academics argued that ancient peoples stayed confined to their regions, Heyerdahl suggested something radical—that migration and contact between faraway cultures happened through daring sea journeys. His ideas were often controversial, but rather than just write books, he built vessels and put his life on the line to prove them.

The Kon-Tiki: A Raft That Changed History

The centerpiece of the museum—and Heyerdahl’s most famous exploit—is the Kon-Tiki expedition of 1947. Together with five companions, he constructed a raft of balsa wood logs and other native materials, based on ancient South American models. Then he sailed it from the coast of Peru across the Pacific Ocean to Polynesia, covering nearly 7,000 kilometers in 101 days.

Walking into the large exhibition hall, I stopped dead in my tracks. There it was: the actual Kon-Tiki raft, preserved in all its weathered glory. At first glance it looks impossibly fragile—ropes tied around rough logs, a thatched hut, and a small steering oar. And yet, this raft had faced storms, sharks, and the endless stretch of ocean.

Surrounding the raft are displays of the crew’s tools, cooking equipment, journals, and photos. You get the sense of just how exposed and vulnerable they were. Nearby, documentary footage plays on a loop—the same footage that became the Oscar-winning film “Kon-Tiki” (1951). Watching the men wrestle with sails, laugh at flying fish, and stare into the vast Pacific gave me chills. It’s not just history—it’s human endurance captured on film.

More than Kon-Tiki: Ra and Tigris

Heyerdahl’s adventures didn’t end in Polynesia. The museum also showcases his later projects:

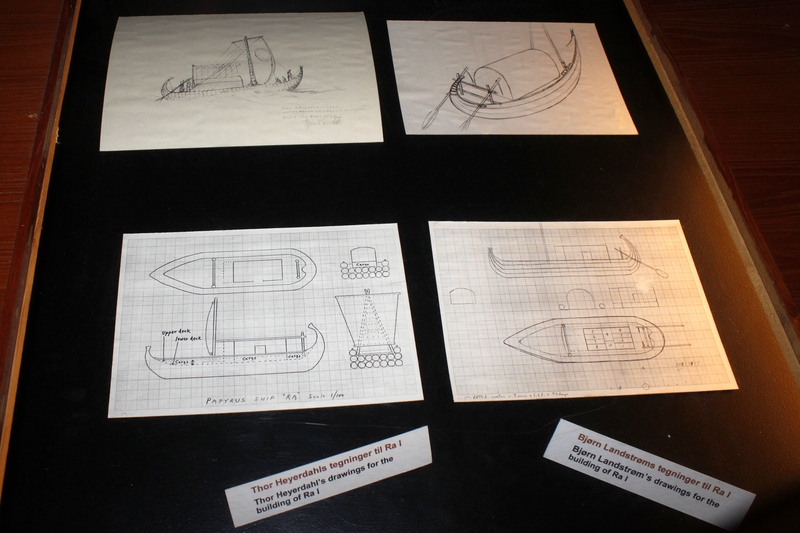

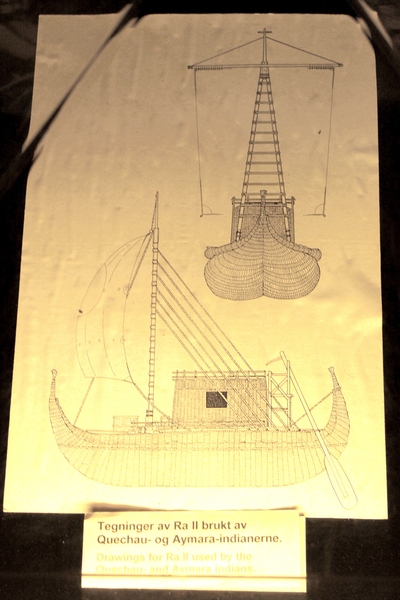

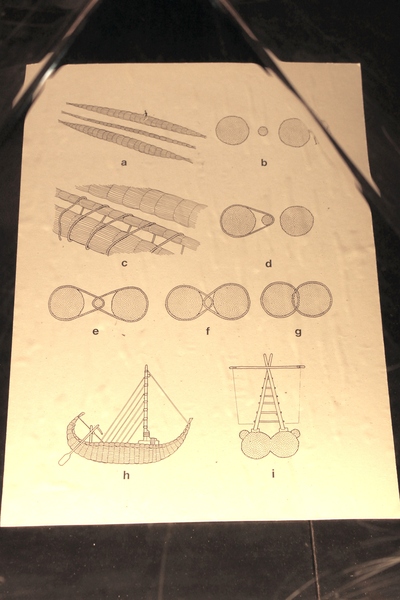

- Ra I and Ra II: Inspired by ancient Egyptian depictions, he built reed boats to test whether people could have sailed from North Africa to the Americas. The first attempt sank, but Ra II succeeded, sailing from Morocco to Barbados in 1970.

- The Tigris: Constructed in 1977 from reeds in Iraq, this ship set out to show that Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley, and Egypt could have been connected by sea. The voyage ended dramatically when Heyerdahl burned the ship in protest against wars in the region, proving that for him, expeditions were also about messages of peace.

Seeing these vessels—or at least remnants and reconstructions—adds depth to the story. Kon-Tiki was not a one-off stunt. Heyerdahl dedicated his life to demonstrating that humans have always been capable of incredible seafaring journeys.

Inside the Museum Experience

The museum isn’t just about vessels. It’s about atmosphere and narrative. Here’s what stood out for me:

- Immersive displays: Life-sized models of the ships, surrounded by maps, photos, and artifacts.

- Film screenings: A schedule of short films and documentaries runs throughout the day. The Kon-Tiki film is the must-see, but there are also screenings about Ra and Tigris. I made sure to catch the Kon-Tiki one mid-visit, which tied the exhibition together perfectly.

- Cultural exhibitions: Displays on Polynesian history, South American artifacts, and oceanic navigation traditions that give context to Heyerdahl’s theories.

- Personal items: His notebooks, letters, and even small souvenirs collected during expeditions. These add a human touch—reminders that he wasn’t just an adventurer but also a husband, a father, and a man driven by relentless curiosity.

The halls are dimly lit, with spotlights on the vessels, creating a sense of reverence. At one point I found myself simply standing still, staring at Kon-Tiki, imagining what it must have been like to wake up every morning to nothing but waves in all directions.

The Practical Side

- Location: The museum sits on Bygdøy peninsula, which is also home to the Fram Museum, the Viking Ship Museum (currently being renovated), and the Maritime Museum.

- Getting there: You can reach Bygdøy by bus 30 from central Oslo, or by ferry during the warmer months. I recommend the ferry—the short journey gives you a beautiful view of the Oslo Fjord.

- Time needed: Set aside 2–3 hours at least. If you want to catch more than one film screening, allow longer.

- Nearby attractions: Since you’re already there, it’s worth visiting the Fram Museum next door, dedicated to polar exploration, for another dose of Norwegian courage and adventure.

Why This Visit Mattered to Me

Leaving the museum, I felt a strange mix of awe and gratitude. Awe, because Heyerdahl’s achievements remain staggering—imagine stepping onto a raft knowing you might never return. Gratitude, because museums like this keep those stories alive and remind us that exploration is not only about geography but about imagination.

Thor Heyerdahl may not have been right about everything—many of his theories are still debated—but he dared to dream big and back those dreams with action. That’s a lesson I carried with me as I boarded the ferry back to the city.

For travelers, the Thor Heyerdahl Museum is more than a collection of boats. It’s a reminder of what human beings can do when they trust curiosity more than fear.